The Rules of the Game

The air in the negotiation room is thick with manufactured tension, a currency he trades in as skillfully as any stock. He watches the beads of sweat on the opposing counsel's brow, the subtle shift of weight from one foot to the other, the almost imperceptible flicker of doubt in his eyes. These are not just tells; they are vulnerabilities, inputs in a complex algorithm running constantly in his mind. He offers a disarmingly warm smile, a practiced gesture of camaraderie that costs him nothing and gains him everything. It’s a move, a calculated play in a game only he is fully aware he’s playing.

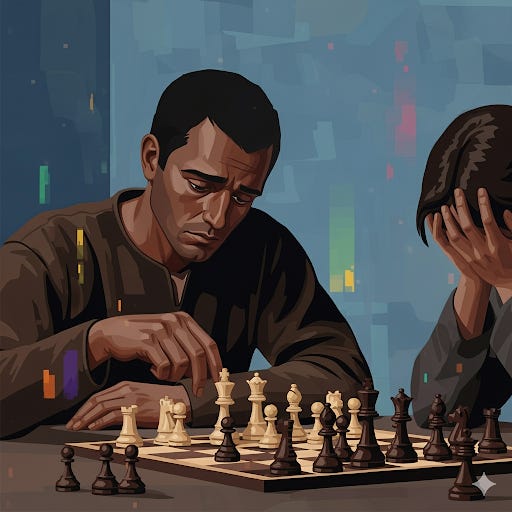

Inside, there is no storm of anxiety, no flutter of empathy for the lives that will be impacted by the fine print he’s so artfully buried. There is a profound quiet, a detached calm that allows for crystalline focus. The world is not a network of relationships but a series of chessboards, each with pieces to be moved, strategies to be deployed, and victories to be secured. He feels the thrill of the win—a clean, sharp surge of dopamine—as the final papers are signed.

Walking out into the bustling street, he is an island of perfect stillness in a chaotic sea, the architect of a reality built to his own specifications, wondering only what game comes next. This experience, this deep and unshakable sense of detachment from the emotional currents that guide others, is the core of what it can feel like to navigate the world with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). It is a profound and often misunderstood experience, one that goes far beyond caricatures of overt criminality into the very wiring of one’s internal world.

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder: More Than a Label

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) is a clinical diagnosis characterized by a pervasive and ingrained pattern of disregarding and violating the rights of others. In this context, "antisocial" does not mean withdrawn or introverted; its literal meaning is more accurate: to be "anti-society," operating against its rules, norms, and ethical considerations. This common misunderstanding is a significant barrier to recognition, as a charming and popular individual who is secretly manipulative might not be seen as having "antisocial" traits, delaying intervention until harmful behaviors escalate.

This pattern of behavior doesn't emerge suddenly in adulthood. A diagnosis of ASPD in an individual aged 18 or older requires evidence of Conduct Disorder before the age of 15. This childhood precursor involves behaviors like aggression toward people or animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness, and serious rule violations. These are not mere teenage rebellion; they are the early manifestations of a neurodevelopmental trajectory where the brain circuits responsible for empathy, impulse control, and moral reasoning may have developed differently. From this perspective, the symptoms are less a conscious choice and more the outcome of a complex interplay between genetic predispositions and adverse early environments, such as childhood abuse, neglect, or chronic chaos.

The Invisible Weight: Living with Antisocial Personality Disorder

To the outside world, life with ASPD might look like a series of impulsive, reckless, and harmful choices. On the inside, it can feel like navigating a world where you are the only one who sees the machinery behind the curtain. The emotional landscape is often muted; feelings like empathy, guilt, and remorse can be profoundly absent. This isn't necessarily a malicious void but can be experienced as a simple lack of intuitive understanding of others' feelings—like trying to read a book written in a language you were never taught.

Common signs and symptoms of ASPD include:

Deceitfulness and Manipulation: A tendency to repeatedly lie, use aliases, or con others for personal gain or pleasure, often masked by a superficial charm or wit.

Impulsivity and Recklessness: A failure to plan ahead and a tendency to act on the spur of the moment without considering the consequences for oneself or others.

Aggressiveness and Irritability: A low tolerance for frustration that can lead to physical fights or assaults.

Consistent Irresponsibility: A repeated failure to sustain work, honor financial obligations, or fulfill parenting roles.

Lack of Remorse: An indifference to or rationalization of having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from someone else.

The internal experience is one of operating on a different frequency. The social contracts that bind people—trust, mutual respect, guilt—can feel like arbitrary and illogical constraints. Life is a strategic endeavor, and relationships are often transactional, assessed for their utility in achieving a goal. This is not necessarily born of a desire to cause harm, but from a brain that is wired for reward and personal gain, often with a diminished capacity to process fear or the distress of others.

Spotlight: What's Driving the Distress? ASPD vs. Psychopathy

While often used interchangeably in popular culture, Antisocial Personality Disorder and psychopathy are not the same. Think of ASPD as the observable blueprint of a house and psychopathy as the unique, internal wiring and foundation.

ASPD is the formal clinical diagnosis found in the DSM-5. Its diagnosis relies heavily on a pattern of observable behaviors: breaking laws, lying, impulsivity, and aggression. An individual can be diagnosed with ASPD based primarily on a long history of criminal and irresponsible actions.

Psychopathy is a more specific psychological construct, not an official diagnosis, that includes the behavioral aspects of ASPD but also emphasizes a core set of personality traits. These are profound deficits in emotion and interpersonal connection, such as a complete lack of empathy, a grandiose sense of self-worth, shallow emotions, and a callous, predatory nature.

The key difference is this: most people who meet the criteria for psychopathy will also meet the criteria for ASPD, but only a fraction of those with ASPD meet the criteria for psychopathy. A person can be diagnosed with ASPD for being impulsive and getting into fights, but they might not have the cold, calculating, and emotionally vacant core that defines the psychopath. This distinction is crucial, as the core personality traits of psychopathy are a much stronger predictor of future violence and resistance to treatment.

Beyond the Diagnosis: How Antisocial Personality Disorder Impacts Relationships, Work, and Life

The fundamental disconnect from societal norms and emotional understanding has a devastating ripple effect. Stable, healthy relationships are incredibly difficult to maintain because they are built on a foundation of trust and mutual empathy that may be absent. Partners and family members often feel used, manipulated, and emotionally neglected, leading to toxic and volatile relationship dynamics. For a parent with ASPD, the inability to form secure attachments can create a chaotic and traumatizing environment for children, perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of distress.

Professionally, the same traits that can lead to short-term success—charm, ruthlessness, and a focus on personal gain—often sabotage long-term stability. Consistent irresponsibility, impulsivity, and conflicts with authority make steady employment a significant challenge. This leads to high rates of unemployment, financial instability, and profound involvement with the criminal justice system. A staggering 47% of male prisoners and 21% of female prisoners meet the criteria for ASPD, highlighting the immense societal cost of the disorder.

It is a deeply painful paradox. The very behaviors that are deployed as survival strategies—the manipulation to feel in control, the impulsivity to seek stimulation, the aggression to establish dominance—are the ones that ultimately lead to isolation, failure, and incarceration. This is the central tragedy of ASPD: the relentless pursuit of winning the game often results in losing everything that truly matters.

Finding Your Footing: Pathways to Empowerment

While ASPD is one of the most challenging disorders to treat, change is not impossible. The path forward is not about "curing" the disorder but about managing its most harmful expressions and building a life with more stability and less destruction. Treatment is often mandated by the legal system and focuses on harm reduction and behavioral containment rather than fostering empathy, which may not be a realistic goal.

For the Individual: Therapy can be a space to learn, in a purely logical sense, how certain behaviors lead to negative consequences. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can help in identifying the distorted thought patterns that lead to harmful actions, while Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) offers skills for managing intense emotions and impulsivity. The goal is pragmatic: to reduce aggression, maintain sobriety, and decrease criminal behavior because it is in your own self-interest to do so.

For Families and Partners: If you are in a relationship with someone with ASPD, it is absolutely crucial to seek your own support. Living with this disorder can be emotionally and physically taxing. Therapy can help you learn to set firm, enforceable boundaries and protect your own well-being. It is not your responsibility to "fix" the person, but it is your right to keep yourself safe.

Therapeutic Approaches: The most effective treatments are often structured and behavioral. Contingency Management, which provides tangible rewards for positive behaviors, has shown promise, especially for co-occurring substance use disorders. While no specific medications are approved for ASPD, mood stabilizers and some antidepressants may be used to manage symptoms like aggression and impulsivity.

An Actionable Tool: The "Pause, Play, Rewind" Practice

Impulsivity is a core driver of the negative consequences of ASPD. This micro-exercise is designed to insert a critical moment of reflection between an impulse and an action.

Pause: The moment you feel the urge to act—to send the angry text, to walk off the job, to take the risk—physically stop. Clench your fists and then release them. Take one deep breath. This is the Pause.

Play the Tape Forward: In your mind, quickly visualize the most likely outcome of your impulsive action. Don't censor it. See the argument, the job loss, the arrest. See the immediate gratification, but then see what comes after. This is Playing the Tape.

Rewind to a Different Choice: Now, rewind the mental tape. Identify one small, different action you could take instead. It doesn't have to be perfect. It could be leaving the room, waiting ten minutes before responding, or saying nothing at all. This is the Rewind. The goal is not to become a different person overnight, but to practice creating a gap between impulse and action.

The Unseen Gift: Reframing Your Journey with Antisocial Personality Disorder

Living with ASPD can feel like being the only one who knows the world is a game. This perspective, while the source of immense pain and destruction, also contains a paradoxical gift: a radical, unsentimental clarity. You see the mechanics of systems, the levers of influence, and the often-hypocritical rules of social engagement that others miss. The challenge, and the only path to a different kind of victory, is to learn how to use this insight not to exploit the game, but to change how you play it.

The game doesn't have to be about dominating others. It can become an internal one: the challenge of outsmarting your own destructive impulses, the strategic victory of holding a job for another month, the complex move of learning to use your sharp focus to build something instead of tearing it down. This is not about developing feelings you may not have; it is about recognizing, with cold, hard logic, that a different strategy leads to a better outcome. It is a transformation of the game from one of conquest to one of self-mastery.

A Note for Therapists and Helping Professionals

Treating individuals with ASPD requires a paradigm shift from traditional insight-oriented therapy to a pragmatic, behavioral, and risk-management framework. The therapeutic alliance is often tenuous; prioritize consistency, clear boundaries, and a non-judgmental but firm stance. Countertransference is a significant risk, as feelings of frustration, helplessness, or even being manipulated are common. Regular peer supervision is essential. Focus on concrete, measurable goals such as reducing recidivism, managing co-occurring substance use, and improving prosocial behaviors through skill-building and contingency management. Acknowledge that the goal may not be empathy, but rather the cognitive understanding that pro-social behavior is ultimately in the client's own self-interest.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Crisis Information: If you are in crisis or are experiencing suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the following resources:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

The Trevor Project: 1-866-488-7386 (for LGBTQ youth)